Julia Ward Howe – Battle Hymn to Mother’s Day Proclamation

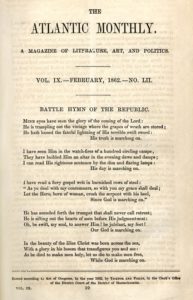

READING The Battle Hymn (1861) by Julia Ward Howe published in The Atlantic in February 1862

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord:

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord:

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He hath loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword:

His truth is marching on.

I have seen Him in the watch-fires of a hundred circling camps,

They have builded Him an altar in the evening dews and damps;

I can read His righteous sentence by the dim and flaring lamps:

His day is marching on.

I have read a fiery gospel writ in burnished rows of steel:

“As ye deal with my contemners, so with you my grace shall deal;

Let the Hero, born of woman, crush the serpent with his heel,

Since God is marching on.”

He has sounded forth the trumpet that shall never call retreat;

He is sifting out the hearts of men before His judgment-seat:

Oh, be swift, my soul, to answer Him! be jubilant, my feet!

Our God is marching on.

In the beauty of the lilies Christ was born across the sea,

With a glory in his bosom that transfigures you and me:

As he died to make men holy, let us die to make men free,

While God is marching on.

READING Mother’s Day Proclamation (1870) by Julia Ward Howe

https://youtu.be/TG73A1SkU1c

Arise, all women who have hearts, whether your baptism be that of water or of tears! Say firmly: “We will not have great questions decided by irrelevant agencies, our husbands shall not come to us, reeking with carnage, for caresses and applause.

“Our sons shall not be taken from us to unlearn all that we have been able to teach them of charity, mercy and patience. We women of one country will be too tender of those of another country to allow our sons to be trained to injure theirs.”

From the bosom of the devastated earth a voice goes up with our own. It says, “Disarm, disarm! The sword is not the balance of justice.” Blood does not wipe out dishonor nor violence indicate possession.

As men have often forsaken the plow and the anvil at the summons of war, let women now leave all that may be left of home for a great and earnest day of counsel. Let them meet first, as women, to bewail and commemorate the dead. Let them then solemnly take counsel with each other as to the means whereby the great human family can live in peace, each learning after his own time, the sacred impress, not of Caesar, but of God.

In the name of womanhood and of humanity, I earnestly ask that a general congress of women without limit of nationality may be appointed and held at some place deemed most convenient and at the earliest period consistent with its objects, to promote the alliance of the different nationalities, the amicable settlement of international questions, the great and general interests of peace.

SERMON

In the United States, the origins of Mother’s Day go back to 1870, when Julia Ward Howe – an abolitionist best remembered as the poet who wrote “Battle Hymn” – worked to establish a Mother’s Peace Day. Howe dedicated the celebration to the eradication of war, and organized festivities in Boston for years.

But how did a woman born in 1819 in New York City and raised by a strict Calvinist father with firm ideas about the appropriate role and behavior of both girls and boys end her life as a champion of abolition, women’s suffrage, and the author of the Mother’s Day Proclamation?

Julia’s father – Samuel Ward – was a successful New York banker.

Julia’s mother – Julia Ward – died when young Julia was only five years old. So, Julia was raised by her father and the teachers he hired to educate his daughters. The boys were sent off to private boarding school for their more important education. Julia often lamented her life as a female in her father’s house as she was controlled and limited by his ideas of proper womanhood. Young Julia wanted a full and deep education and she desperately wanted to be a writer.

Her father said “No.” – to both requests.

Yet, Julia and her sisters were educated. They had tutors come to the house to engage them in their studies. She learned classics and three languages and was quite good with history and math by the time she reached her 12th birthday. Julia excelled in her music studies. She had piano and voice lessons and became quite an accomplished singer. When her brothers returned from their school on holiday, frustrated and bored with what they were forced to study, Julia admitted that since taking charge of her own studies, she was happier and better educated than most boys. Still, she felt trapped – describing her life as one of imprisonment with her father as her jailer.

Following the dictates of the day, Julia accepted a marriage proposal from Samuel Howe and they were married in 1843. Theirs was a difficult partnership. While they loved each other, Samuel could never understand nor support his wife’s deep longing to be a writer and a public figure in her own right. He believed that a wife ought to derive all happiness and fulfillment from devotion to and support of her husband and children. This was impossible for Julia. The result was that both of them were frustrated and unhappy throughout much of their marriage.

Julia did accompany Samuel on many of his trips and lectures.

Among others, Julia and Samuel were friendly with Theodore and Lydia Parker, Horace and Mary Mann, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller and William Ellery Channing. All of these notable Americans were Unitarians. Julia had maintained devotion to the Calvinism of her father until, through the influence of people she respected and her own effort, she turned toward Unitarianism. In her diary she wrote, “I studied my way out of all the mental agonies which Calvinism can engender and became a Unitarian.”

In the presence of these Unitarians and by their own convictions, Samuel and Julia became abolitionists. The Howes attended the church of Theodore Parker for a time. She then met James Freeman Clarke, another Unitarian minister. His sermons and his ministry were a bit more pastoral and poetic and he became her regular minister. James Freeman Clarke was with the Howes when they went to Washington, D.C. in 1861 to visit a Union Army encampment and help with the Sanitary Commission. One of the many songs being sung by the Union soldiers was John Brown’s Body.

You may remember the lyrics –

John Brown’s body lies a-moldering in the grave

But his soul goes marching on

The stars above in Heaven are looking kindly down

On the grave of old John Brown

He captured Harper’s Ferry with his nineteen men so true

He frightened old Virginia till she trembled through and through

They hung him for a traitor, they themselves the traitor crew

But his soul goes marching on

Glory, Glory, Hallelujah

Glory, Glory, Hallelujah

Well, Clarke thought the words too rough and he suggested to Julia that she write lyrics better suited to the popular tune. That night, while sleeping in her hotel room, the words came to her in a single rush. She got out of bed and, careful not wake her sleeping children, she grabbed the stub of a pencil wrote the words in their entirety. When morning came and she could actually see what she wrote, she made two quick adjustments to the words and was finished with what she called, “The Battle Hymn.” Confident that her poem had merit, she sent it off to a friend of hers at The Atlantic magazine. He added ‘of the Republic’ to the title and published it in the February issue of The Atlantic. He paid her $5.

At age 42, Julia Ward Howe had a poem that would make her famous and her words – adapted and updated sometimes – are familiar to most of us now.

Here is what we ought to understand about this poem and about Julia during the years of the Civil War.

She was an abolitionist and a firm supported of the Union cause

She came to regard the Civil War as a kind of Holy War that was a battle between freedom and slavery; God, she felt, was on the side of freedom.

The words are an indictment of the Confederacy, and they are harsh.

The final words are: As he (Christ) died to make men holy, let us die to make men free,

While God is marching on.

Not a poem for the feint of heart or wavering loyalties.

This was a Union song, and the Confederate sympathizes hated it.

The poem and the song followed Julia for the rest of her life.

With fame came speaking engagements and introductions to a wide range of people and ideas.

She was asked frequently to lead the assembly in reciting The Battle Hymn.

While she never shied away from her poem or from its fame, she did come to change her views about war.

She saw the carnage of war – both in the American Civil War and the wars of Europe.

She was already involved with the changing roles and expectations of women in America. She supported women’s suffrage and became a leader of the New England Woman Suffrage Association.

The combination of her life experience and the development of her own social and political and religious identity moved her in new directions. She affirmed the equality of women and men. She became much less controlled by her husband – much to his frustration and disappointment – and moved in her own circles with her own point of view.

In the years following the end of the Civil War, Julia came to understand how horrible war is for everyone. The loss of human life was staggering. The misery of survivors was also staggering. Her growing sense of a separate and honorable womanhood came with a realization that women had a very different experience of war than men had and that women could, and should, play a vital role in preventing war. She embarked upon a campaign to empower women to rise up against the forces of combat and to resist war. Her call to arise was, and is, uniquely suited to women. She believed that men were so indoctrinated against compromise and cooperation that it would fall to women to pursue the means to end all talk or action of war.

In 1870 – ten years after writing the Battle Hymn – Julia issued The Mother’s Day Proclamation… Not a glorification of war, but a prayer and an admonition against war.

Arise all women who have hearts! These are powerful words and they do not soften the bold claim against war.

Women will not allow their sons to be taken

Women will not receive their husbands who stink of blood and carnage

Women of one nation shall be too tender toward women of another nation to send their sons to kill the sons of other mothers

From the blood soaked and devastated earth the cry goes up DISARM

Her proclamation ends with a call for women to leave behind everything and take counsel together – to mourn their dead and to create a new and different way of resolving differences that does not require the violence and death of war.

Her vision was for an annual gathering of women from all nations to promote understanding and peace. She earnestly believed that women, women of tender hearts, could, and must, successfully promote peace.

On June 2, 1872, the first Mothers Peace Day was celebrated in Boston, Massachusetts. For the next thirty years Americans celebrated this day in June.

As we know, eventually, the observance was tamed and moved to May.

The modern Mother’s Day, with its apolitical message, emerged in the early 20th century, with Howe’s original intent largely erased from the mainstream consciousness. Howe’s vision of an antiwar mother’s call to action for peace was watered-down into an annual expression of sentimentality.

Today …

I want to lift up the amazing person Julia Ward Howe.

She began as the daughter of a strict Calvinist banker father.

She lived a relatively privileged life in New York City.

She married well.

She had six children.

She lived more than 90 years.

And yet – she often felt as though she was imprisoned in a life that had no joy or value or fulfillment. Her father and then her husband were her jailers.

She struggled to find her own voice and her own personhood.

She suffered from depression and hopelessness, yet she always pulled herself back from the brink of total despair and went on doing what she felt her life called her to do – often in secret and often without personal attribution.

As she grew into full womanhood, she loosed the chains that bound her.

She studied and reasoned her way out of Calvinism and into Unitarianism – and she never looked back.

At 42, she wrote The Battle Hymn and supported the Union cause and the resulting war.

At 52, she delivered the Mother’s Day Proclamation in which she rejected the value of war for any cause.

She grew in knowledge and understanding and faith throughout her life.

In the last decade of her life, she continued to lecture and work for peace and for women’s suffrage.

She died content in her intentions though sad that the work she cherished remained unfinished.

Her work remains unfinished. Women did achieve the franchise in 1919.

Peace remains elusive.

This Mother’s Day, I am so very conscious of need for a counsel of women, and men, whose tender hearts would not allow their children to kill the children of other parents.

Our earth remains blood-soaked and devastated.

We have not gained the courage to disarm.

We have not replaced violence with counsel.

We have not yet come to understand that peace is more valuable than the spoils of war and that the cost of war in human lives and scorched earth can never be recovered. Julia Ward Howe’s call to arise and disarm echoes in our hearts and minds today. There is work to be done.

For those of us who love what this holiday means today, let us be glad.

For those of us who are simply sad on this day, let us be tender-hearted.

For those of us whose family is complete and loving without a mother, let us be appreciative and supportive.

For all of us, let us remember that Mother’s Day is also a day to arise and disarm and work for peace.

Blessed Be. I Love You. Amen.